以下内容来源于新英格兰医学杂志。

Presentation of Case

Dr. Christine M. Parsons (Medicine): A 75-year-old woman was evaluated at this hospital because of arthritis, abdominal pain, edema, malaise, and fever.

Three weeks before the current admission, the patient noticed waxing and waning “throbbing” pain in the right upper abdomen, which she rated at 9 (on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating the most severe pain) at its maximal intensity. The pain was associated with nausea and fever with a temperature of up to 39.0°C. Pain worsened after food consumption and was relieved with acetaminophen. During the 3 weeks before the current admission, edema developed in both legs; it had started at the ankles and gradually progressed upward to the hips. When the edema began to affect her ambulation, she presented to the emergency department of this hospital.

A review of systems that was obtained from the patient and her family was notable for intermittent fever, abdominal bloating, anorexia, and fatigue that had progressed during the previous 3 weeks. The patient reported new orthopnea and nonproductive cough. Approximately 4 weeks earlier, she had had diarrhea for several days. During the 6 weeks before the current admission, the patient had lost 9 kg unintentionally; she also had had pain in the wrists and hands, 3 days of burning and dryness of the eyes, and diffuse myalgias. She had not had night sweats, dry mouth, jaw claudication, vision changes, urinary symptoms, or oral, nasal, or genital ulcers.

The patient’s medical history was notable for multiple myeloma (for which treatment with thalidomide and melphalan had been initiated 2 years earlier and was stopped approximately 1 year before the current admission); hypothyroidism; chikungunya virus infection (diagnosed 7 years earlier); seropositive erosive rheumatoid arthritis affecting the hands, wrists, elbows, and shoulders (diagnosed 3 years earlier); vitiligo; and osteoarthritis of the right hip, for which she had undergone arthroplasty. Evidence of gastritis was reportedly seen on endoscopy that had been performed 6 months earlier. Medications included daily treatment with levothyroxine and acetaminophen and pipazethate hydrochloride as needed for cough. The patient consumed chamomile and horsetail herbal teas. She had no known allergies to medications, but she had been advised not to take nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs after her diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Approximately 5 months before the current admission, the patient had emigrated from Central America. She lived with her daughter and grandchildren in an urban area of New England. She had previously worked in health care. She had no history of alcohol, tobacco, or other substance use. There was no family history of cancer or autoimmune, renal, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or cardiac disease.

On examination, the temporal temperature was 37.1°C, the heart rate 106 beats per minute, the blood pressure 152/67 mm Hg, and the oxygen saturation 100% while the patient was breathing ambient air. She had a frail appearance and bitemporal cachexia. The weight was 41 kg and the body-mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) 15.2. Her dentition was poor; most of the teeth were missing, caries were present in the remaining teeth, and the mucous membranes were dry. She had abdominal tenderness on the right side and mild abdominal distention, without organomegaly or guarding. Bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy was palpable. Infrequent inspiratory wheezing was noted.

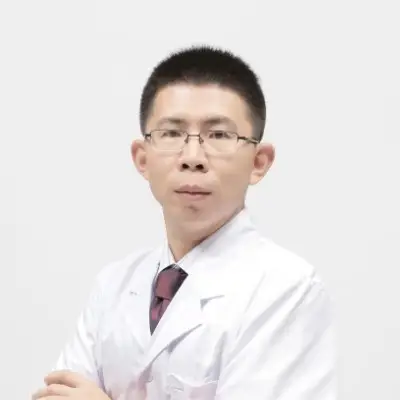

The patient had swan-neck deformity, boutonnière deformity, ulnar deviation, and distal hyperextensibility of the thumbs (Fig. 1). Subcutaneous nodules were observed on the proximal interphalangeal joints of the second and third fingers of the right hand and on the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fourth finger of the left hand. Synovial thickening of the metacarpophalangeal joints of the second fingers was noted. There was mild swelling and tenderness of the wrists. She had pain with flexion of the shoulders and right hip, and there was subtle swelling of the shoulders and right knee. Pitting edema (3+) and vitiligo were noted on the legs. No sclerodactyly, digital pitting, telangiectasias, appreciable calcinosis, nodules, nail changes (including pitting), or tophi were present. The remainder of the examination was normal.

Figure 1

Photograph of the Hands.

The blood levels of glucose, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, globulin, lactate, lipase, magnesium, and phosphorus were normal, as were the prothrombin time and international normalized ratio; other laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. Urinalysis showed 3+ protein and 3+ blood, and microscopic examination of the sediment revealed 5 to 10 red cells per high-power field and granular casts. Urine and blood were obtained for culture. An electrocardiogram met (at a borderline level) the voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy.

Table 1

Laboratory Data.

Dr. Rene Balza Romero: Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, performed after the intravenous administration of contrast material, revealed scattered subcentimeter pulmonary nodules (including clusters in the right middle lobe and patchy and ground-glass opacities in the left upper lobe), trace pleural effusion in the left lung, coronary and valvular calcifications, and trace pericardial effusion, ascites, and anasarca. The scans also showed slight enlargement of the axillary lymph nodes (up to 11 mm in the short axis) bilaterally and a chronic-appearing compression fracture involving the T12 vertebral body.

Dr. Parsons: Morphine and lactated Ringer’s solution were administered intravenously. On the second day in the emergency department (also referred to as hospital day 2), the blood levels of haptoglobin, folate, and vitamin B12 were normal; other laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. A rapid antigen test for malaria was positive. Wright–Giemsa staining of thick and thin peripheral-blood smears was negative for parasites; the smears also showed Döhle bodies and basophilic stippling. Antigliadin antibodies and anti–tissue transglutaminase antibodies were not detected. Tests for hepatitis A IgG and hepatitis C antibodies were positive. Tests for hepatitis B core and surface antibodies were negative. A test for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and type 2 (HIV-2) was negative.

Findings on abdominal ultrasound imaging performed on the second day (Fig. 2A and 2B) were notable for a small volume of ascites and kidneys with echogenic parenchyma. Ultrasonography of the legs showed no deep venous thrombosis. An echocardiogram showed normal ventricular size and function, aortic sclerosis with mild aortic insufficiency, moderate tricuspid regurgitation, a right ventricular systolic pressure of 39 mm Hg, and a small circumferential pericardial effusion. Intravenous hydromorphone was administered, and the patient was admitted to the hospital.

Figure 2

Imaging Studies of the Abdomen and Hands.

On the third day (also referred to as hospital day 3), nucleic acid testing for cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, and hepatitis C virus was negative, and a stool antigen test for Helicobacter pylori was negative. An interferon-γ release assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was also negative. Oral acetaminophen and ivermectin and intravenous hydromorphone and furosemide were administered.

Dr. Balza Romero: Radiographs of the hands (Fig. 2C through 2F) showed joint-space narrowing of both radiocarpal joints and proximal interphalangeal erosions involving both hands. Radiographs of the shoulders showed arthritis of the glenohumeral joint and alignment suggestive of a tear of the right rotator cuff. A radiograph of the pelvis showed diffuse joint-space narrowing of the left hip, without osteophytosis, and an intact right hip prosthesis.

Dr. Parsons: Diagnostic tests were performed, and management decisions were made.

Differential Diagnosis

Dr. Beth L. Jonas: This patient is a 75-year-old woman who recently emigrated from Central America. She presented to this hospital with a multisystem disease involving the respiratory, gastrointestinal, renal, and musculoskeletal systems. Her medical history is notable for seropositive erosive rheumatoid arthritis and multiple myeloma, which had been treated with melphalan and thalidomide. Relevant clinical features on presentation include unintended weight loss and cachexia, axillary lymphadenopathy, serositis, cytopenia in two cell lines, hypocomplementemia, and elevated serum free kappa and lambda light-chain levels (with a normal free light-chain ratio) with no monoclonal spike. The white-cell count was elevated, but she had no eosinophilia. CT images of the chest showed scattered subcentimeter pulmonary nodules. With respect to the patient’s anemia, no schistocytes were present, the haptoglobin level was normal, and the iron studies were unremarkable. These findings, in combination with the elevated ferritin level, indicate anemia of chronic inflammation. The renal findings are most salient in the context of the patient’s hypertension, anasarca, elevated cystatin C level, active urinary sediment with proteinuria in the nephrotic range, and small, echogenic kidneys on ultrasonography.

In constructing a differential diagnosis, I will consider medication use, cancer, infectious disease, and autoimmune disease. Medications can be eliminated as the cause of this patient’s illness, since she was taking only levothyroxine, acetaminophen, and the antitussive agent pipazethate.

Cancer

The patient has a history of multiple myeloma, which may manifest with a multisystem disease involving the kidneys, but serum protein electrophoresis showed no monoclonal protein. Given the presence of nephrotic syndrome in the context of multiple myeloma, systemic immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis would be highest on the differential diagnosis with respect to cancer; however, the patient’s normal light-chain ratio makes this diagnosis unlikely. The development of myeloid neoplasms, such as acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, and myeloproliferative neoplasms, is important to consider in the context of previous treatment with alkylating agents,

1 which this patient had received. However, the peripheral-blood smear showed no findings that would indicate a hematologic cancer, and such a diagnosis would not explain the patient’s acute kidney injury with nephrotic-range proteinuria.

Infectious Disease

Several features of this patient’s case warrant special consideration, including her history of immunosuppression due to rheumatoid arthritis and to previously treated myeloma, along with the fact that she had emigrated from Central America, where certain infections may be prevalent. Infection with hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, HIV-1 and HIV-2, cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus,

H. pylori, and

M. tuberculosis can be ruled out on the basis of laboratory studies. A rapid antigen test for plasmodium species was reported to be positive, but this assay has a known cross-reactivity with rheumatoid factor.

2 Moreover, the thick and thin peripheral-blood smears were negative. Thus, malaria would be an unlikely diagnosis.

The patient has a history of infection with chikungunya virus, an arbovirus transmitted by a mosquito vector that has been responsible for large epidemics in the Americas since 2013.

3 Acute symptoms include fever, rash, arthralgia, and myalgia. The development of a chronic arthritis that may meet the classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology, has been reported in up to 60% of patients infected with chikungunya virus.

4,5 In the context of this discussion, I considered whether chikungunya virus infection could be the cause of this patient’s symptoms, since this infection occurred before the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. However, the degree of erosion and loss of joint space that was visible on radiographs would be most unusual for arthritis associated with chikungunya virus infection and would not explain the renal manifestations.

Strongyloidiasis is a helminth infection (caused by

Strongyloides stercoralis) that is widespread in developing countries. Infection usually occurs through contact with soil, and most affected persons are asymptomatic. However, in immunosuppressed persons, strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome or a disseminated infection can develop as a consequence of accelerated autoinfection.

6 The clinical presentation of strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome can include gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, constipation, nausea, or vomiting), respiratory symptoms (cough, dyspnea, or wheezing), and rash due to migration of larvae through the subcutaneous tissues. Of note, only a minority of patients present with eosinophilia. Several case reports describe the development of nephrotic-range proteinuria, thrombotic microangiopathy, and IgA vasculitis in patients with strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome.

7-9 However, strongyloidiasis would not explain this patient’s cytopenias and hypocomplementemia.

Autoimmune Disease

The patient has a 3-year history of rheumatoid arthritis, although her clinical features of swan-neck deformity, boutonnière deformity, and joint instability suggest a longer duration of disease. We do not know whether she had received previous treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biologic agents, but the possible use of such treatments may be a consideration with respect to her progression of disease and overall degree of immunosuppression. The blood levels of rheumatoid factor and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies were elevated, and radiographs of the hands showed erosive disease, although there was a relative paucity of metacarpophalangeal findings. A review of systems was negative for dry mouth, but her physical examination showed poor dentition and dry mouth — findings that make secondary Sjögren’s syndrome a consideration.

Renal disease can occur in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. The two most typical presentations are tubulointerstitial nephritis and, less commonly, nephritic syndrome (membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis related to cryoglobulinemia). Tubulointerstitial nephritis may manifest with renal disease of varying severity, usually with a bland urinary sediment and often with abnormalities of tubular function such as distal renal tubular acidosis. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis caused by cryoglobulinemia is the most common glomerular disease associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. Although nephrotic-range proteinuria can occur with Sjögren’s syndrome, it is relatively uncommon.

10 Renal disease is uncommon in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and is usually related to coexisting cardiovascular conditions. Medications used in the treatment of autoimmune disease — mainly nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs — may be associated with renal disease, but I would not expect the presence of an active urinary sediment, as was seen in this patient.

Amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis, a condition that is rare in the era of aggressive management of rheumatoid arthritis, has been described in patients with severe, long-standing seropositive erosive rheumatoid arthritis. Serum amyloid A (SAA) is a protein that is produced in the liver in response to chronic inflammation associated with interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in the context of chronic infections, autoimmune disease (classically rheumatoid arthritis), autoinflammatory disease, and cancers including renal cell carcinoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. 11 Signs and symptoms of AA amyloidosis are related to the deposition of the protein in organs, and patients often present with multisystem signs and symptoms. The kidney is the organ that is most often affected, but deposition can occur in the heart, gastrointestinal tract, nervous system, musculoskeletal system, and lungs. Proteinuria is the first clinical manifestation in almost 95% of patients with AA amyloidosis, and 50% of affected patients present with nephrotic syndrome. 12 The urinary sediment is generally bland, and complement levels in the blood are normal. AA amyloidosis remains on the differential diagnosis in this patient, but it would not completely explain her renal disease.

Hypocomplementemia

The key to this case is understanding the cause of this patient’s hypocomplementemia. Hypocomplementemia can be due to decreased complement production in the context of liver disease, congenital complement deficiency, or increased complement consumption resulting from activation of the innate immune system. This patient has no history of chronic liver disease and her laboratory test results indicated good hepatic synthetic function. Classical complement deficiency (including C4 deficiency) that begins early in life is associated with autoimmune disease, and early C3 deficiency is characterized by severe pyogenic infections. It would be unusual for a patient of this age to be deficient in both C3 and C4 without earlier clinical consequences. I therefore concluded that the hypocomplementemia in this case was related to complement consumption.

Rheumatic diseases that may be associated with prominent renal manifestations include antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis, systemic sclerosis with renal crisis, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, antiglomerular basement membrane disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Of those conditions, SLE would be the most likely to be manifested by an active urinary sediment and nephrotic-range proteinuria with consumption of both C3 and C4 in the context of fever, thrombocytopenia, and serositis. This patient’s fever, thrombocytopenia, and serositis also fit with this diagnosis.

13

Because the patient has long-standing seropositive erosive rheumatoid arthritis, a diagnosis of AA amyloidosis is strongly suspected. Moreover, given the presence of thrombocytopenia, hypocomplementemia, and an active urinary sediment, I would recommend a kidney biopsy to evaluate for lupus nephritis and AA amyloidosis.

Dr. Beth L. Jonas’s Diagnosis

Overlap syndrome of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus with amyloid A amyloidosis.

Pathological Discussion

Dr. Claire Trivin-Avillach: Testing for autoimmune antibodies was performed. A test for antinuclear antibodies was positive at a titer of 1:5120 with a homogeneous pattern, and a test for anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies was positive at a titer of 1:2560.

The diagnostic procedure in this case was a core-needle biopsy of the kidney. Examination of the specimen with light microscopy revealed 20 glomeruli, 45% of which were globally sclerosed, along with fibrosis involving approximately 60% of the interstitium and tubular atrophy. Diffusely enlarged glomeruli with thickened capillary walls and an expanded mesangium were weakly positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining; the glomeruli stained pale blue on Masson’s trichrome staining. Congo red staining revealed metachromatic salmon-colored deposition involving the glomeruli, the blood-vessel walls, and the interstitium, which was associated with apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light (

Fig. 3A). In addition, mesangial and endocapillary hypercellularity was identified in approximately 30% of the nonsclerosed glomeruli and was associated with karyorrhexis (

Fig. 3B). One cellular crescent was also detected. These features are characteristic of active proliferative glomerulonephritis.

Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed prominent granular staining for IgG (4+), IgM (4+), C3 (3+), C1q (3+), IgA (1+), kappa (3+), and lambda (3+) along the glomerular basement membranes and within the mesangium, as well as focal granular deposits of IgG and C3 along the tubular basement membrane (

Fig. 3C and 3D). Additional immunofluorescence studies showed strong positivity (4+) for SAA within the glomeruli, the blood-vessel walls, and the interstitium (

Fig. 3E), whereas staining for beta

2-microglobulin, transthyretin, and apolipoprotein A1 was faint.

Electron microscopy revealed the presence of subendothelial and mesangial electron-dense deposits (with no substructure identified) adjacent to randomly arranged fibrils (measuring 8.2 to 10.6 nm in diameter) within the glomerular basement membranes and the mesangium (

Fig. 3F). Glomerular endothelial cells appeared reactive and contained tubuloreticular inclusions, features that were suggestive of interferon-mediated activation.

The findings on Congo red staining were characteristic of amyloidosis with typical birefringent material. The strong positivity of SAA within the deposits as compared with the faint staining of other reactants identified the type of amyloid as SAA, which is consistent with the patient’s history of rheumatoid arthritis. The biopsy also showed an immune complex–mediated proliferative glomerulonephritis with a “full house” pattern (defined as positivity for the three immunoglobulin classes IgG, IgM, and IgA and the two complement components C3 and C1q, in reference to the “full house” hand in a poker game). Immune complex–mediated proliferative glomerulonephritis has been reported in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were receiving anti–TNF-

α therapy,

14 which was not the case in this patient. The positive test for hepatitis C antibodies prompted consideration of hepatitis C–related membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. However, taken together, the negative nucleic acid test for hepatitis C virus, the full house pattern on immunofluorescence, the tubular basement membrane deposits, and the positive test for anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies favor a diagnosis of lupus nephritis of at least class III (defined as focal proliferative glomerulonephritis), according to the criteria of the International Society of Nephrology and the Renal Pathology Society, superimposed on AA amyloidosis.

Pathological Diagnosis

Proliferative lupus nephritis of International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society class III, superimposed on amyloid A amyloidosis.

Discussion of Management

Dr. Pui W. Cheung: On the basis of the finding of echogenic kidneys on ultrasonography and the findings of extensive interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy on kidney biopsy, we know that this patient has advanced chronic kidney disease that is unlikely to be reversible. The patient is also noted to have a markedly lower glomerular filtration rate (GFR) than that predicted by the blood creatinine level owing to the presence of cachexia, and this is substantiated by the cystatin C–based GFR and a 24-hour creatinine clearance of 22 ml per minute per 1.73 m

2 of body-surface area. The typical induction therapy for stage III or IV lupus nephritis consists of high-dose glucocorticoids and either mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide. Other reasonable alternatives for initial therapy include mycophenolate mofetil in combination with either a calcineurin inhibitor or belimumab, or cyclophosphamide in combination with belimumab.

15 Hydroxychloroquine is also recommended as part of the therapy, since it has shown benefits in improving the response to treatment and reducing disease flare.

16 Mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide have similar efficacy with respect to clinical response, which includes a reduction in proteinuria and either an improvement in renal function or stabilization of renal function; the risks of infections and adverse events associated with these medications are also similar.

17,18

Given the severity of the lupus nephritis with overlying AA amyloidosis from active rheumatoid arthritis, the treatment options proposed were high-dose glucocorticoids and rituximab with either mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide.

19 After discussions with multidisciplinary consultants from rheumatology, infectious diseases, and nephrology, lingering concerns were raised about infection and patient frailty; ultimately, the decision was made to initiate high-dose glucocorticoid therapy in combination with mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, and hydroxychloroquine.

The patient’s mycophenolate mofetil dose regimen was inconsistent owing to gastrointestinal side effects, and the treatment was eventually withheld because of pancytopenia and fever. Unfortunately, her kidney function worsened, and renal replacement therapy was initiated within 3 weeks after the start of the induction therapy. The cause of her renal failure was thought to be disease progression, compounded by hemodynamically mediated tubular injury in the context of infection. While the administration of mycophenolate mofetil was stopped, treatment with rituximab was continued, with slow tapering of the glucocorticoid dose at the direction of the rheumatologist. She remained dependent on dialysis and was deemed to have end-stage kidney disease after 3 months of dialysis.

Dr. Lisa G. Criscione-Schreiber: The patient has SLE with nephritis, seropositive erosive rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic AA amyloidosis. AA amyloidosis is rare owing to the availability of effective therapies for rheumatoid arthritis and is managed through aggressive treatment of inflammation due to rheumatoid arthritis. Reports addressing the management of rheumatoid arthritis–induced AA amyloidosis generally cite stability of end-organ damage caused by AA amyloid as evidence of effective management of the condition (through treatment of the inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis). Methotrexate, the cornerstone of treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, is contraindicated in this case owing to the presence of kidney disease. The alkylating agent cyclophosphamide has been reported to be effective for the treatment of AA amyloidosis from rheumatoid arthritis

20 and has known efficacy in patients with lupus nephritis, both of which make it a viable treatment option. Rituximab has also been reported to be effective for managing rheumatoid arthritis–induced AA amyloidosis,

21 is approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, and is used for manifestations of SLE, including thrombocytopenia and nephritis. Although anti–TNF-

α agents, abatacept, and Janus kinase inhibitors are reported to be effective for the treatment of AA amyloidosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis,

22 recent publications have coalesced on the ability of anti–interleukin-6 therapy to block interleukin-6–induced hepatic production of SAA.

23-25

The overlap of seropositive erosive rheumatoid arthritis and SLE (sometimes termed “rhupus”) usually resembles rheumatoid arthritis more than SLE; manifestations include thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, an elevated blood level of C-reactive protein, and the presence of marginal erosions on radiographs. 26 In contrast, SLE without seropositive erosive rheumatoid arthritis characteristically manifests with thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate but usually not an elevated C-reactive protein level; in addition, nonerosive inflammatory arthritis with reversible deformities is commonly observed. This patient had a mixed laboratory profile, on the basis of the results of antinuclear antibody and anti–double-stranded DNA antibody tests. The challenge of treating an overlap syndrome of rheumatoid arthritis and SLE is choosing disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs that are effective and safe in both conditions. This patient’s most severe disease manifestation is lupus nephritis; therefore, the treatment regimen must target nephritis along with the AA amyloidosis and inflammatory arthritis.

As noted earlier, current induction therapy for lupus nephritis includes either mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide. Mycophenolate mofetil may provide inadequate treatment of the rheumatoid arthritis and amyloidosis, whereas cyclophosphamide would treat the lupus nephritis, has possible efficacy for treatment of the AA amyloidosis, and would treat the rheumatoid arthritis. Rituximab could be added to cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil to treat the rheumatoid arthritis and resultant AA amyloidosis and could also possibly help treat the lupus nephritis. The addition of anti–interleukin-6 therapy to mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide is an intriguing option that may effectively treat the rheumatoid arthritis and subsequent AA amyloidosis. The addition of belimumab to mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide has been reported to improve renal response in patients with lupus nephritis,

27 as has the addition of voclosporin to mycophenolate mofetil.

28 However, belimumab is ineffective for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, and voclosporin has not been studied in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or in those with a GFR of 45 milliliters per minute or less. The high-dose glucocorticoids that are used in induction therapy for lupus nephritis will effectively manage this patient’s inflammatory arthritis and probably also the subsequent AA amyloidosis. Finally, it is important that every patient with lupus nephritis receive hydroxychloroquine, which improves the treatment response to induction therapy.

29

Follow-up

Dr. Parsons: The patient’s hospital course was further complicated by suspected immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, for which she received intravenous immune globulin. Her pancytopenia and arthritis ultimately abated. Unfortunately, she did not have renal recovery and continues to receive hemodialysis. After a prolonged hospital course, she was discharged home.

Final Diagnosis

Overlap syndrome of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by proliferative lupus nephritis, superimposed on amyloid A amyloidosis.

京东健康互联网医院

京东健康互联网医院

网站导航

网站导航

579

579

4

4

24

24

36

36

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0